The Story of the West Midland Bird Club: Parts 1 &2 - Graham Harrison, Jim Winsper and Janet Harrison

- Richard Stonier

- Dec 2, 2025

- 68 min read

Updated: Dec 22, 2025

Introduction

Welcome to this, the first two Instalments of the Club’s Story (or History), covering the period 1929-1959. We do not see this as a definitive record, but rather “a work in progress”, which is why we have chosen to produce it electronically. By posting it on the Club’s website, our hope is that readers will send us their own contributions. Whilst few of you will be old enough to remember these early years, we’d love to hear of your experiences, recollections etc. for possible inclusion in future Instalments. It is essential that we gather as much detail as possible now, before it’s too late, so that the Club has a thorough record of its history to mark its centenary in 2029.

Important as a straightforward factual history would be, we feel it could prove rather boring. So, to understand how the Club has developed over the past ninety-odd years and to gain an appreciation of its achievements and influence, we have attempted to set this against the social, economic and environmental contexts of the time, the individuals involved and, above all, some of the changes in the region’s birdlife that have occurred along the way. We have chosen to consider these aspects decade by decade. Within each decade we have attempted to record events in chronological order, though to maintain continuity this has not always been possible.

During the time span involved, society has evolved from being formal to being informal. So, in the early days members were mostly referred to by their surnames, whereas today first names and even abbreviations are commonly used as well. Since we believe all members of the Club are equal, we have chosen to use the names by which everyone is generally now known. In doing so, we hope we will not have caused any offence, but please accept our apologies if we have.

Ideally, we would have liked to present continuous sets of data for matters such as membership, finance, indoor and field meetings, and branch activities, but this hasn’t always been possible. For example, we could illustrate the growth in membership when there were just two categories, but it became more complicated with the introduction of husband-and-wife or partners categories and impossible following the introduction of Standard and Inclusive categories. Financial matters have also proved problematical, with decimalisation and varying rates of inflation. In the absence of early copies of the Club’s Bulletins, there are also some significant gaps in our knowledge, particularly regarding increases to subscriptions.

We are aware that the late Alan Richards had been writing a history of the WMBC and we feel that our Story of the Club, dedicated to his name, is an appropriate way to commemorate the huge contribution that he made. Alan had asked one or two members to read some drafts and what appears to be a very early incomplete draft has come to light. It confirms our belief that Alan was writing an autobiography rather than a history of the Club, but it has provided a few snippets of information from the early years, such as W. E. Groves’ forenames being were Wellington Ernest.

Alan suggests that a Miss Celia James was one of the invitees to Mr Groves’ house for that very first meeting. However, in his report of the Silver Jubilee, Mr Norris wrote about “how it all began” and said Mr Groves had supplied a detailed report of the early years and said he had invited Messrs Alexander, Henry and Wallis to his home on November 1st 1929 – no mention of Miss James although she is known to have been an early member of the Club.

The 1920s

Our story begins in the final year of a decade that had been one of turmoil, with the General Strike of 1926 and the Wall Street crash in November 1929. In those days natural history centred more around the study of specimens in museums and private collections, with less attention given to observations in the field. True, the RSPB had been founded in 1889, the National Trust acquired its first nature reserve at Wicken Fen in 1899 and Charles Rothschild had formed the Society for the Promotion of Nature Reserves in 1912. But the primary focus of such interest as there was in birds remained on egg collecting and shooting, with the mantra of the time being “what’s hit is history, what’s missed is mystery”. The pressure this put on our birdlife was intensified by the increased mechanisation of farming during the decade, which began to change many traditional habitats.

The precursors of local, or regional, bird clubs were those established by the Oxford Ornithological Society (founded 1921) and the Cambridge Club (founded 1925) and it may have been these that were the inspiration for something similar in Birmingham. In his biography of Horace Alexander, Duncan Wood says “W.E. Groves invited four people to his (Edgbaston) home early in 1929: they met to share their recent observations and to talk about birds”. The four included Horace Alexander.

However, in the 1954 Annual Report (No. 21) Tony Norris said “It was on November 1st 1929 that Mr W.E. Groves invited to his house H.G.(Horace) Alexander, H. Henry and C.W.K. Wallis and at that first meeting it was decided to form a club for comparing notes and observations of bird life.” Since Messrs Groves and Alexander were at the Jubilee Celebration we presume the above to be accurate, with Mr Groves himself being the fourth member.

It was certainly at this meeting that a club, which subsequently became known as the Birmingham Bird Club, was formed. And one of the founder members was Horace Alexander – surely the doyen of British birdwatching, combining as he did the pleasures of birdwatching with the satisfaction of contributing to ornithological science – principles which have underpinned the development of the Club ever since.

The 1930s

The Great Depression and the outbreak of World War II left an indelible impression on a decade which otherwise brought significant benefits to those with jobs. The collapse of many traditional industries during the 1920s left a legacy of widespread unemployment which persisted into this decade across much of the country. Along with the South-east, however, the West Midlands bucked this trend to some extent. Here the skilled workforce that had proved its worth during the first World War now adapted to new, emerging industries such as the manufacture of motorbikes and cars as well as embracing new technologies centred around electricity. Many families came to the region in search of work, particularly from Ireland and Wales, swelling the population and increasing the need for more housing.

For the unskilled, however, unemployment remained a scourge and life for them was a constant struggle to put food on the table. A trip on the number 70 tram from Birmingham to the Lickey Hills would have been an unimaginable luxury, or at best a once-a-year highlight. Any contact they might have had with birds was most likely to have been songbirds in cages or homing pigeons in the lofts that many built in their gardens or back yards.

For the middle and upper classes, though, it was a different story. Electrical household appliances, such as vacuum cleaners and washing machines, had taken away some of the drudgery of housework, while a shorter working week and paid holidays meant more leisure time. Increased spending power also meant they were able to afford luxuries such as a telephone and, if you were very fortunate, even a car.

Enthusiasm for health and fitness saw an increase in outdoor recreational activities, but birdwatching remained a minority pursuit, confined to the well-off. Among the reasons for this were perhaps the perception that it was a rather ‘sissy’ activity; that it was an expensive pursuit; and that it was difficult to get information and get to good birdwatching places. Hints that these might have been obstacles can be found in the Club’s Annual Reports.

In 1937, for example, it was said “Perhaps the chief event of the year was the invasion of rare grebes and other unusual waterfowl after the bitter winds at the end of January. The telephones and motor cars of Bird Club members were very busy during the early days of February.” Only the well to do would have had telephones and motor cars in those days. And even for those with a car, the journey to Bittell Reservoirs would have been slow and possibly fraught with difficulty, as a 30mph speed limit had been introduced in 1935 and cars at that time were unreliable and prone to breakdown.

Following the 1929 inaugural meeting, a further meeting was held early in 1930 in a small room hired at the Grand Hotel in Birmingham, at which it was decided to hold further meetings approximately every two months. Who paid for the room at such a prestigious venue remains a mystery. The procedure at these meetings was for each member in turn to give an account of his or her ornithological experiences since the previous gathering. Others were invited to join the Group on the recommendations of founder members, but to avoid meetings becoming too protracted, membership was restricted in number, with some sources saying twelve and others fifteen. A few visitors were also invited from time-to-time, but they were not permitted to take an active part. Mr Groves chaired all these meetings and, in fact, occupied all offices of the Club, except that of Editor. until 1946.

In his biography of Horace Alexander, Duncan Wood (2003) gives an insight into the early years of the Club and the following is an extract from his accounts.

“No doubt a good deal of information about Midland birds was pooled at these meetings, but it remained private and unrecorded – and thus unavailable to science – lest it come to the notice of collectors. Groves was obviously suspicious of strangers and kept the Club small to avoid infiltration by members of the collecting fraternity. Horace Alexander, though, did not regard strangers with suspicion. His wide acquaintance amongst his contemporary ornithologists taught him that there were collectors, or ex-collectors, who were excellent ornithologists and trustworthy to boot.

Horace realised that the Club would have to widen its horizons if it was to serve the interests of ornithology and birdwatching in the Birmingham region; and he used his authority as its leading field ornithologist to persuade the Club to do so.”

Duncan also recalls that Horace Alexander studied Bittell Reservoir intensively prior to its being taken over by the sailing club. He also visited Belvide, as did Arnold Boyd from Cheshire who had been making occasional visits there since the 1920s. Indeed, Duncan recalls that he and Ralph Barlow were privileged to join Horace’s New Years’ Day outings to Belvide. He described these as serious expeditions, made at first by bus, or by train to the station which then existed at Gailey, but later in Horace’s Morris Cowley.

Following the precedents set by the Oxford and Cambridge club, the Club produced its first Annual Report in 1934, with Horace Alexander as Editor-in-Chief, assisted by Duncan Wood and Ralph Barlow. This embraced the whole of Warwickshire and Worcestershire, as Horace was in touch with observers in these counties. At this juncture we should perhaps explain that recording was done on historical county boundaries (known by botanists as Vice Counties), so Birmingham, Coventry, Solihull and Sutton Coldfield were included in Warwickshire and Dudley in Worcestershire.

This first Report included Classified Notes of the records received; dates of Migrant Arrivals and Departures; an article on observations at Bartley Reservoir; and a Report on Special Species, namely Dipper, Nightingale, (Common) Redstart, (Eurasian) Wryneck and Corncrake. Thus, we have an early indication of where members were birdwatching – Bartley being a newly constructed drinking-water supply reservoir that had only been fully filled as recently as 1931. It also told us some of the species considered to have a restricted distribution at that time. Interestingly it also began with an apology from the editor for its delay and incompleteness – sentiments which subsequent editors were frequently forced to express!

With just a few members, the Classified Notes were naturally sparse, but the list of Special Species elicited some illuminating comments. The views expressed were mostly subjective and sometimes appeared to be contradictory. (Common) Nightingales, for example, were said to be “common in all fox-coverts and suitable spots” around Rugby, whereas a mere twelve miles away around Coventry numbers were said to be “less than twenty years ago”. More objective information came from Worcestershire, however, when, in 1934, 40 singing birds were noted in 20 square miles – 30 in scrub, five in gardens and five in roadside spinneys, but none in large woods! One notable feature, though, was how many observers reported declines in the species concerned – an early indication of trends that sadly have continued ever since.

With very few changes, this first Report established the format for all subsequent Annual Reports. As the membership has grown, so too have the Classified Notes (now the Systematic List) from a modest dozen pages then to around 200 today. The Club has always maintained a strong emphasis on research and has been keen to publish analytical articles – a policy which it will no doubt continue in the future.

Duncan Wood also mentioned that “Horace promoted birdwatching in the field and willingly shared his expertise and enthusiasm with members of the younger generation, who were somewhat impatient with the restricted outlook of the original Club.” Among these youngsters were the brothers William and Hugh Kenrick and Tony Norris – of whom the latter was destined to become a prominent figure in the Club’s history. Other names mentioned amongst the 27 Members and Correspondents at this time that were later to regularly feature in the development of the Club were Ralph Barlow, Mr Betts, Freddie Fincher and Tony Harthan.

Other organisations also influenced the Club’s development, not least The British Trust for Ornithology, which Max Nicholson had formed in 1933. The ensuing years were to see a close relationship develop between the BTO and the Club, as will become apparent later.

In 1935 the Club introduced an Associate Membership class, with a subscription of five shillings (25p in today’s money), which went towards the cost of the Annual Report and meetings. By the second half of the decade, periodic lectures for members and associates were also being arranged in rooms at the Midland Institute, the Natural History Society and the Chamber of Trade.

Another major step this year was to extend the Club’s area to embrace South Staffordshire (which in those days included present day Sandwell, Walsall and Wolverhampton). The northern boundary was defined to the west of Stafford by the old railway line which ran beyond the county to Newport and Wellington (both in Shropshire), whilst to the east it followed the Rivers Sow and Trent as far as Burton-on-Trent. This was a significant move, as it brought the canal feeder reservoirs at Belvide, Chasewater and Gailey and the extensive heath and woodland of Cannock Chase into the Club’s ambit. As mentioned earlier, Horace Alexander had been visiting Belvide for several years, as had Arnold Boyd from Northwich in Cheshire – a journey of 50 miles for the latter, which in those days must have been even more exacting than that described earlier. In a land-locked region without a coastline, reservoirs were an obvious attraction, so to keep the location secret from collectors, they chose to refer to Belvide as “Bellfields”.

Whilst reservoirs were the favoured haunts for most members, some were beginning to discover new places. Mr Groves, for example, drew attention to the “attractiveness” of Curdworth Sewage Farm (now Minworth Sewage Works) – such works being well known amongst birdwatchers in those days, with Nottingham and Wisbech being outstanding examples. In this region, the sewage farms at Whittington (Staffs) and later Baginton (Warks) were also regularly visited by local birdwatchers, who were occasionally rewarded with something unusual. Other areas mentioned as “providing interesting records” were the Enville District, the Lickey Hills, Wyre Forest, Randan Wood (which was Freddie Fincher’s local patch) and parts of the Severn and Avon Valleys (which would have been well known to Tony Norris and Tony Harthan). The Report editors mentioned as a matter of regret, however, that they had received no records for Sutton Park – a large area of heathland and woodland north-east of Birmingham which had been gifted firstly by Henry VIII to John Vesey, Bishop of Exeter, and hence to the Council for the benefit of the poor inhabitants of Sutton Coldfield!

The early Annual Reports demonstrated the fastidious detail in which notes were taken, with many containing references to nests being found. In some cases this may have been a legacy (or even continuation) of skilled egg collectors at work. A more generous view, however, might be that, unlike today, observers were prepared to devote more time watching the birds they had found since, with no communication network, they would have been oblivious to any other, more unusual species that might have been around. In any event they would probably have lacked the time and transport to get to see them. Moreover, the optics of the day, if any, would have required close views to confirm identification and such views could only be obtained with patience, often in the vicinity of a nest. The reports tell us very little about what optics were available – some of which were probably ex-military binoculars or draw telescopes. The latter, of course, required some effort to hold them steady and often resulted in you lying flat on your back with a support to raise your head while you rested the ‘scope on a raised knee.

Close views and positive identification, of course, could also be obtained through ringing and a new feature in the 1936 Report was a Ringing Recoveries Map. The ringing of birds in Britain dated back to the introduction of the Ringing Scheme in 1909, but the practice relied on the construction of elaborate traps of which we shall hear more later.

Around this time, according to the Annual Report, a draft constitution for the Club was under consideration, but we have been unable to find any further information on this. (see also comments in 1940s Chapter).

Members’ attention was also drawn to a request in British Birds for information about song periods and several members submitted information on this. The BTO suggested (Common) Pochard, Grey Wagtail, Lesser Redpoll and Little Owl for study in 1936, so these were added to the list of Special Species. Amongst the more unusual observations were those of a Waxwing feeding on hawthorn berries overhanging a much-used road at Northfield, which “even a steamroller failed to disturb” and a Diver found at 2.00 am on the tram lines at Selly Oak! – both localities being suburbs of Birmingham.

Papers on the birds of Edgbaston Park and Rotton Park (now Edgbaston) Reservoir – both reveal the range of birds that could be found within a mile or two of Birmingham city centre, while in 1937 the long-awaited paper on the Bird Life in Sutton Park appeared, highlighting the species to be found on the edge of the city.

Even at this early time members were beginning to express concerns about changes in the environment and the effect they were having on birdlife. Agriculture was becoming mechanised and an article in the 1939 Report revealed that between 1933-39 the number of Lapwings on a 150-acre (60 ha) Worcestershire farm fell from 10 to none between 1933-39 as a result of the land being “much improved by good management and Government Fertility schemes”.

In addition, the first signs of development pressures were beginning to arise from the buoyant economy and need for more housing referred to earlier – pressures which were to intensify after the war. For example, the 1938 Report noted “it is gratifying to record that a stretch of country near the Bittell Reservoirs, threatened with building by the proximity of the Austin factories, has been secured by public subscription and placed under (the care of) the National Trust; a neighbouring portion has also been secured against the builder”. It was around this time too that the idea of a green belt around our cities first emerged, though it would be some thirty years before one for the West Midlands was finally confirmed!

Ultimately, these pressures were to bring one benefit to members, however, as concrete became an increasingly popular building material. The alluvial sands and gravels underlying the valleys of the Avon, Severn, Trent and Tame were an ideal source of raw materials for this and landscapes in areas such as the Tame Valley were progressively scarred by quarries. Once these quarries were exhausted and pumping ceased, the workings gradually flooded, creating new wetland habitats. Before long these were attracting a range of wildfowl and waders which were otherwise scarce in the landlocked Midlands. Consequently, they became the favoured haunts of many Club members as will be seen later.

A landmark publication in 1938 was T. Smith’s Birds of Staffordshire – the first of a trilogy of county avifauna to appear within ten years. Incorporated within it was an addendum contributed by A. W. Boyd, which included some records from Club members, notably Horace Alexander, but only those that had been published previously in British Birds. No other records were mentioned, and T. Smith was not a member, which perhaps explains why he made no mention of the Club at all. Clearly the Club had still to prove its credentials to those living north of Birmingham.

By the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the Club had 15 members and 60 associates, whilst a further 19 people contributed to the Annual Report – an increase of 350% over the decade.

The 1940s

More than any other, this was a decade of two halves – the first half dominated by the war and the second recovering from it.

The War Years

No one was immune to the impact of the war, which affected virtually every aspect of everyday life, with air raids, blackouts, food shortages and rationing of almost every essential item. Many places suffered bomb damage, but none more so than Coventry, which was devastated by the blitz of November 14th 1940. By comparison it is often thought that Birmingham got off lightly, but nothing could be further from the truth. From August 1940 onwards the city was bombed relentlessly. But, because its factories were so important to the war effort, efforts were made to deny the enemy any knowledge of its success by adopting a voluntary embargo on the mention of Birmingham, which the media sometimes reported simply as “a Midlands town”.

By the time the 1939 Annual Report was published in 1940 (the dates of Annual Reports, of course, referring to the year they cover, not the year of publication) we were several months into World War II and much had changed. Many members had joined the armed forces and were seeing service overseas, or in different parts of the country. Horace Alexander and his assistant, Duncan Wood, had stood down from their positions and Anthony Harthan had taken over as Editor of the Annual Report.

Virtually all non-essential activities had been brought to an abrupt end, or at least severely restricted, but somehow, against all the odds, the Club managed to keep going. Despite the restrictions, meetings continued to be held in members’ homes, and a few were also said to have been held outdoors, though whether these were just informal group gatherings, or actual field meetings is unclear. We assume from the travel and other restrictions in force at the time that the former is most likely.

That the Club managed to keep going at all in such difficult circumstances might possibly have been because certain key figures were in reserved occupations. Whether this applied to Tony Norris and Tony Harthan we do not know, but these two gentlemen were responsible for much of the content of the wartime reports, which was naturally very limited. One noteworthy event occurred in 1940, when Tony Norris married Cicely Hurcomb, daughter of The Lord Hurcomb. The significance of this will become clear later.

Not only did the Club manage to keep going, but even more amazingly, Anthony Harthan managed to produce an Annual Report every year throughout the war. Extracts from his editorials give a good indication of the difficulties he encountered. In 1941 he wrote “in order to economise paper and meet the increased cost of production under war conditions, this Report is compressed”; in 1942 “this Report is produced under difficulties due to war conditions, which include cost, economy of material, and the scattering of active Members and Associates over various parts of the world. However, it is hoped that the few who are left to carry on the work of the Bird Club will have made this Report worthwhile, and of interest to our absent members”; and in 1943 “On account of restricted space due to necessary economies, it has not been possible to include in this Report all the interesting notes and papers that were sent in. These were more numerous than last year, which is particularly gratifying considering that no effort is being made to increase the numbers of Members and Associates while the Club is suffering from wartime difficulties”. He also added in the latter Report “printing difficulties are again the cause of the somewhat late production of this Report” To elaborate on the difficulties he faced, printing restrictions and paper shortages, severely limited the number of copies that could be produced, with several copies of at least one issue (1942 from recollection) having to be hand-written!

Birdwatching by the few members that were still around was naturally confined to their local patches and this resulted in some interesting accounts of the impact the war was having on certain habitats and their birdlife.

Intensive bombing with incendiaries had sparked off innumerable fires and water to extinguish these became increasingly scarce, especially as some water mains had been damaged. Among the auxiliary resources to which fire crews turned were the canals and this in turn led to a drawdown of supplies in the feeder reservoirs. This might explain the exceptional circumstances recorded at Rotton Park Reservoir (Edgbaston Reservoir as it is now known) by the Club’s Chairman, W.E. Groves.

Living literally just round the corner from the reservoir, he said in 1941 that “extensive drainage under war conditions has entirely altered the character of the site. The normal bed of the reservoir is now covered with grasses, sedges etc. and is intersected with several small streams fringed with water plants. Between these streams are large areas of persicaria, goosefoot, bur-marigold etc. The reduction of the water area to a few acres generally excludes the ducks which have been of outstanding interest to the birdwatcher in the winter of recent years ... … This transformation has proved attractive to many birds which probably would have passed on under usual conditions.” He goes on to add that “Yellow Wagtails have been numerous; large flocks of (Common) Linnets feed on seeds; many (Eurasian) Skylarks and Meadow Pipits are present in winter; and (Common) Snipe and even Jack Snipe have visited the boggier areas.”

Three years later he said “Conditions changed very much for the worse in 1944. The ground was badly trodden by grazing cattle and probably few of the nesting birds were able to bring off young. Most of the cover for (Common) Snipe as well as the seeding plants were flattened. A further disaster befell the ground-nesting birds in the summer, when the Reservoir was opened in the afternoons free and the ‘amusement park’ became active again. The crowds – particularly at holiday times – spread over and picnicked on the grass and the small numbers of Yellow Wagtails which then remained – then busy with their nests – had a very bad time.”

The effect of war was also felt in the countryside, though the impacts were very different, as the surveys of Old Hills Common, near Malvern, undertaken in 1942 by H.J. Tooby and published in the 1944 Report, reveal. He estimated there were 161 breeding pairs of all species in some 135 acres (55ha) of common land. During the next two years 85 acres (34ha), or almost two-thirds of this area, was cleared, ploughed and brought into cultivation as part of the war effort. As a consequence, the estimated breeding population fell by 43%. The number of breeding pairs on the 50 acres (20ha) that remained uncultivated, however, increased by 70%, giving an overall estimate of 190 breeding pairs – an increase of 19%. He went on to comment that “(Common) Linnets, warblers, Song Thrushes and Turtle Doves had deserted the cultivated portions of the common: Blackbirds, (Common) Chaffinches and Yellowhammers appeared more adaptable, being content with very little cover; and Tree Pipits increased slightly on the cultivated portion.” Commenting on this paper, the Editor, Tony Harthan, remarked that it “seems to indicate that the ploughing up of commons may lead to an increase of nesting birds rather than the reverse, when the latter might be expected.”

These are just two examples of how the Club’s members continued to observe and document the effect of wartime regulations on the environment and birdlife. A third, less reassuring example, again from Worcestershire, concerned the Cirl Bunting. Described in the 1940 Report as “sparingly distributed over some areas of south Worcestershire and north Gloucestershire”, it was seemingly unable to adapt to the changing environment and was ultimately lost. Given their later significance to the Club, reference must also be made of the first breeding of Black Redstarts, when a pair nested on the University of Birmingham in 1943. This was followed by a male that regularly sang from the top of a bomb-damaged building in the city centre, at the bottom end of New Street. Interestingly, colonisation of Inner London began with a male, which coincidentally also sang around London University in 1939, with others breeding around bomb-damaged buildings from 1942.

Whilst some changes were bad, others were quite beneficial. The imperative of war saw the construction industry switch from building houses to new munitions factories, airfields and other essential infrastructure, which of course sustained sand and gravel extraction and created new habitats. Meanwhile other changes were occurring naturally and in 1941 A.J. Martin provided the first records from a newly discovered pool at Upton Warren.

By the end of the war membership stood at 71 compared to 75 at the outbreak. The similarity of these figures, though, masks a considerable turnover in members. As would be expected, wartime losses were considerable and only 45 (60%) of those who were members in 1939 were still members in 1945. This means that 26 new members (37% of the total membership) were recruited during the war – a remarkable achievement considering the circumstances and the fact there had been no initiatives or promotion to encourage new members to join.

Post War Years

Not surprisingly, the end of hostilities heralded an era of euphoria and hope for a lasting peace. There was also an anticipation of a better future that was summed up by the slogan ‘Good times are just around the corner’. In truth, though, it was to be well into the next decade and beyond before the good times really arrived.

On the political front it was marked by a spate of landmark legislation that established the National Health Service; the New Towns Act of 1946 that much later resulted in Redditch becoming a New Town; the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947 that through numerous subsequent amendments has shaped the pattern of land use as we know it today, even requiring permission to create nature reserves or erect hides. From the point of view of nature, perhaps the most significant was the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949, which established the principle of Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs) and under which Cannock Chase became an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The 1947 Planning Act also introduced Green Belts and the principle of compensation and betterment – the latter which, following subsequent amendment, was how the Club secured the future of its Ladywalk Reserve as we shall see much later.

Despite the ongoing hardships, there was unsurprisingly a widespread enthusiasm for change and the Club, no doubt swept up in the general euphoria of the time, engaged in a period of considerable growth and development. In 1945, it embarked on a complete reorganisation. An indication of what was to come had been provided in the editorial of the 1943 Report, which said “when it is practicable to introduce the proposed constitution – which was in draft at the commencement of the war – it is confidently expected that the scope and activities of the Club will be much enlarged. There is every indication that the interest in bird life is increasingly widespread.”

A major move was to acknowledge the Club’s wider influence by changing the name from the ‘Birmingham Bird Club’ to the ‘Birmingham and District Bird Club’. Then, early in 1946 the constitution and rules, that had been drafted before the war, were finally approved and a committee was elected along with the officers listed below. We have been unable to trace a definitive copy of this constitution.

The previous distinction between fifteen members and the rest of the Club was abolished and membership was opened to anyone genuinely interested in birds, including Junior Members for the first time. Prospective members were required to complete an application form and enrolment was subject to approval by the Committee. Where possible, introduction by an existing member was preferred and in the case of a Junior Member this was deemed essential (see the 1948 Annual Report). The membership subscription was 10/- (a mere 50p in today’s money!).

The following were appointed as officers of the Club: Horace Alexander as President; W. E.

Groves as Vice-President, Acting Secretary and Treasurer; W. E. Kenrick as Chairman: A. J. Harthan continued as Editor and Mr Lindsay Forster became Meetings Secretary. A committee of eight, including two ladies, was also appointed to assist with management of the Club’s affairs. In the autumn of 1946 Messrs Groves and Harthan asked to be relieved of their respective duties and the roles of Secretary and Editor were taken up by C. A. Norris, or Tony as he was generally known. The new rules were adopted at the AGM in February 1947, but with an amendment to change the Club’s name to the ‘Birmingham and West Midland Bird Club’. A move to delete the word ‘Birmingham’ from the name was referred back to the Committee but subsequently rejected. Unfortunately, we have not found a definitive copy of the rules, but the notes about the Club which were included at the end of the 1949 Report give some idea of its constitution and activities. They were produced as a promotional leaflet and are shown below.

Unfortunately, we have not found a definitive copy of the rules, but the notes about the Club which were included at the end of the 1949 Report give some idea of its constitution and activities. They were produced as a promotional leaflet and are shown below.

From this it can be seen that, in addition to its Annual Reports, the Club was now holding indoor and field meetings; had established branches at Kidderminster and Studley and had plans for more branches. The 1945 Report referred to a library being in the course of formation, to be administered by the Meetings Secretary, but as there was no further mention in later Reports, we do not know whether this venture ever came to fruition.

By now the Club was flourishing as never before, with membership doubling from 71 at the end of the war to 142 by 1946 and 219 the following year – a threefold increase in just two years. In addition, there were now 39 junior members.

Indoor meetings had resumed in 1945, when the four that were held attracted an average audience of 27. The following year, eight meetings were attended by an average of 38, but we have been unable to trace the subjects and speakers.

Field Meetings had also resumed on a modest scale in 1945, with 20 members attending an evening visit to Edgbaston Park and several other local meetings being arranged by members. On a sad note, the passing of C.W.K. Wallis robbed the Club of one of its founder members.

The second and third parts to a trilogy of county avifauna followed closely on one another – with the publication of The Birds of Worcestershire by Tony Harthan in 1946 and Notes on the Birds of Warwickshire by Tony Norris in 1947. Although both were personal rather than Club ventures, coming from current and former editors they obviously relied heavily on the Club’s archive of records.

1947 proved to be a landmark year in many respects. It will long be remembered as a record year for weather, with extremes of cold and heat; rain and drought. It began with one of the worst winters on record, as snow that fell on January 22nd remained lying until March 16th – a record 53 days, with some drifts on higher ground persisting well into April. There were severe shortages of fuel, as coal stocks were frozen at the pitheads; power cuts left homes in the dark; and factory workers were having to work by candlelight. Food also became scarce as the huge snow drifts disrupted distribution by rail and road, leaving many isolated villages cut-off for days. Crops were ruined and livestock perished, resulting in long queues at the shops for such basics as bread, and even potatoes were rationed. To compound matters there was a mounting financial crisis that prompted the Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, to call again for sacrifice akin to wartime and admit “I have no easy words for the nation. I cannot say when we shall emerge into easier times”.

The harsh winter inevitably had a severe impact on birds. With open waters frozen solid, wintering wildfowl were forced to vacate the region, and Grey Herons were especially badly affected. An even earlier snow fall had already caused an exodus of thrushes, notably Fieldfares and Redwings, and many of those passerines that remained sadly perished, especially Long-tailed Tits. Others sought refuse in urban areas where they would not normally have been seen and some, such as Blue and Great Tits were recorded for the first time pecking open the tops of milk bottles to get at the cream.

Rising temperatures in spring finally brought an end to the ‘big freeze’, but the rapid thaw that followed caused widespread flooding and high water levels that resulted in a poor wader passage. Summer was then hot and dry, with August the hottest for sixty years. Generally dry conditions then persisted throughout much of autumn, with spells of fog and another heavy snowfall in November. This incredible year of weather was so aptly summarised by Lindsay Forster in the Annual Report as “almost too much of everything”. Notwithstanding such difficulties, Club members continued to record the region’s birdlife as best they could and by the year’s end 164 species and races had been seen compared with 159 in the previous year.

This was also a momentous year for the Club, when its founding principles were established. Membership increased from 144 to 219 and junior membership from 31 to 39. It was also the year in which the Club began to hold regular monthly meetings in the City of Birmingham Art Gallery – a feature that Tony Norris described as “a privilege that has become of increasing benefit to the Club”. These featured illustrated talks by several eminent naturalists, or the occasional showing of a film of particular interest to members.

An indication of their popularity can be gleaned from the average attendances, which increased from 27 in 1945 to 38 in 1946 and just over 80 this year.

Field meetings were also held at frequent intervals and these of course were of special value to beginners, with special transport usually being arranged. Popular places visited were the Severn Goose Grounds (now Slimbridge), the Wyre Forest, Long Mynd and some of the larger reservoirs.

Towards the end of the year a preliminary meeting was held on November 18th when Messrs Norris, Forster, Lambourne and Rayner met to discuss resurrecting the pre-war Research Committee. Tony Norris was elected Chairman and G.W. Rayner Secretary, while H Kenrick, C Cadbury and L Salmon were proposed as additional members. The primary aims of the Committee were then established and it was agreed that any publications should appear in the Club’s Annual Report, in British Birds and other magazines.

It was also decided that the Committee’s ultimate aim should be to establish an Observatory and Ringing Station and to encourage Club members to carry out their own ringing.

Regarding expense, the Committee said it was “fully aware of the financial problems arising from its activities, but the discussion of these was deferred to a later meeting”. Mr Forster, however, stressed “the need for (proposals) to be established on firm foundations before attempting the more advance inquiries and, with this in mind and realising too the implication of the abolition of the basic petrol ration (sic) which prevents members from travelling far afield,” Bearing this in mind it was resolved to organise a (Common) Starling Inquiry, with the aim of ringing several hundred birds to determine whether or not they were mostly continental birds. Reverting to expense, it was agreed that ringers should pay for their own rings.

Following on from this meeting, the Club’s elected (Main) Committee then endorsed the establishment of the Research Committee. Hereafter the Club was run by two committees, known as the Main Committee and the Research Committee. The latter held its inaugural meeting on December 11th at which it set out its own constitution. There was also a discussion about recording migrant dates and species distribution with quinquennial reviews. Most enthusiastically received, however, was the suggestion for a Christmas Bird Count, which it was thought would be of “tremendous value in ascertaining the winter distribution of the more common species”. In the event it drew 25 responses, which was considered a sufficiently encouraging number to warrant subsequent counts at Easter and Whitsun. Of these two, the former attracted 29 responses, including 10 new participants, but the latter only elicited 15 returns. A comparison of the Christmas and Easter counts showed “a notably reduction in the number of (Common) Starlings, and the increase in those of finches.” Might these counts perhaps be regarded as the precursors of the recently introduced All Dayers?

Regarding migrant arrival dates, it was unanimously agreed that “migrant dates should be preceded each year by a resume of weather conditions at the time of arrival and departure: that extraordinary dates should be listed, but at the same time the average date of arrival and departure for each bird be clearly shown; and that the same species be listed each year even in the absence of any records (though this should be signified).” This procedure has continued with little change in our Annual Reports ever since, though its value has sometimes been questioned.

Another initiative considered by the Committee was that of bird song. It was said “to be desirable for a Club of this size to publish its own chart of song periods and intensity” and Mr. Fincher was asked to explore this possibility. It was also decided to carry out a census on Cannock Chase “in order to find out what birds frequented this wide expanse of high-moorland at the present time”! One member expressed reservations, however, claiming that only “very keen people who are not likely to be disappointed could reasonably well participate in such a census party.” He may well have been right, as the census carried out on June 13th failed to locate any of the much hoped-for grouse.

The Research Committee became central to the Club’s development – a role it was to continue to fulfil for many decades. Fortunately, its minute books have survived and these have proved to be an invaluable source for us in compiling the history from this point onwards.

By 1948 the Branches at Kidderminster and Studley were organising their own indoor meetings, but so far we have not found details of these, whilst ‘some excellent excursions’ were included in the programme of Field Meetings organised for the Parent Club by Hugh Kenrick and Cecil Lambourne – a task later taken over by Talbot Clay.

An insight into the value of these trips, particularly for younger members is given by the

accompanying account of a sighting made during the Club’s visit to Northampton Sewage Farm on October 3rd. It is an extract from the diaries of one of our Junior Members, which have kindly been donated to the Club, and we make no excuse for including this episode in full as it epitomises so much about birdwatching in those days. Firstly, the journey to Northampton would have been equivalent to a trip to the coast today. Secondly, the pleasure a young birdwatcher derived from seeing a new bird is so evident (Ospreys were not as common in those days as they are today). Thirdly, having the use of a telescope tells us a little about the equipment available at the time. Fourthly, the meticulous way he studied the appearance and behaviour of the bird and the methodical way in which he took notes was exemplary. Finally, he later took the trouble to record the event in his diary. Nowadays, of course, modern technology makes life easier. We can just watch, then quickly use a telephoto lens or the camera on a mobile phone and move on! But on the way are we losing some of the enjoyment he so obviously had?

Maurice Larkin lived very close to Rotton Park Reservoir and recorded the movements of birds there almost every day. As a result, he was invited by the Research Committee Chairman to write a report on the influence of weather on duck movements, which he had been studying, as it was thought this might encourage other members to take up some research, and this was published in the 1947 Annual Report.

Returning to the history, an Extraordinary Meeting of the Research Committee was called on February 2nd to deal with the International Wildfowl Committee’s Duck Census just five days later. A list was made of all pools thought to possess more than 50 ducks and, notwithstanding the short notice, letters were posted that evening asking members to visit them. This, or course, marked the beginnings of the regular Wildfowl Counts in which Club members have participated ever since. It also resulted in the ‘discovery’ of the colliery subsidence pools at Alvecote.

Two further proposals were also put to the Research Committee. One was to extend the Club’s area to cover North Staffordshire. This was put to the Main Committee, but we have no record of the response, though presumably it was rejected. The other was to institute seasonal counts on some selected plots of around 10 acres (4 ha) – a proposal which trials showed to be extremely difficult. So, after much discussion it was deferred, pending advice from the Edward Grey Institute and David Lack (BTO) as to its practicality. Since it does not appear to have progressed further, we assume this too was abandoned.

The first Club Bulletin had been produced in May 1947, but it was not until 1948 that it became a regular feature. It quickly became a godsend to the membership as the details of recent sightings provided the most up-to-date information available, enabling members to see at least some of the more unusual birds that were around before they moved on. (Indeed, Alan Richards once confessed that this was a major factor in his joining the Club). The only copy of an early Bulletin that we have found was Issue No 9 in September 1948, an extract from which is shown below. The simple typed sheet is indicative of all that could be achieved under post-war restrictions.

The following year (1949) saw further changes in officers, with Lindsay Forster standing down as Assistant Secretary and the Club’s founder member, Mr W. E. Groves, resigning from his role as Treasurer. In recognition of his contribution, he was presented with a complete set of The Handbook of British Birds (Witherby) and a book token. As long serving members retired from office, however, new faces emerged to help the Club. Two of these were G.W. Rayner and Mike Rogers, who helped compile the 1949 Report – Mike, of course, will be known to many for his outstanding service over many years as Secretary to the British Birds Rarities Committee. Another notable newcomer was Alan Richards, who joined as a Junior Member in 1948 and was destined to become an influential figure in the Club.

Economically the decade closed with a dramatic bombshell as the pound was devalued by 30%. This appeared to have little impact on the Club, however, as membership continued to increase as did the attendance at indoor meetings, which reached an average of 91 in 1949. Most of those who came were probably unaware that many of the speakers were travelling some distance at their own expense. Regrettably we have not been able to find any details of these meetings. Most unusually, though, no speaker had been found for the May Indoor Meeting, so it was decided to hold a Brains Trust, with some pre-prepared questions in case none were received from the floor. As mentioned above, Northampton Sewage Works had been added to the sites visited; and members continued to support national inquires such as the International Wildfowl Inquiry and the Great Crested Grebe Census.

The Research Committee remained as ambitious as ever, with Tony Norris arranging a car journey from his home at Hagley to the Long Mynd as a reconnaissance trip for a proposed field meeting later in the year, providing the Midland Red summer bus service was running to Church Stretton. Following on from the previous year, a second ringing expeditions was also arranged to a Starling roost near Shipston-on-Stour.

Having abandoned seasonal counts on specific plots, it was now decided to pursue a variation by counting the numbers of 30 common, non-aquatic species, to determine seasonal variations in numbers. Contributors to the Annual Report were invited to participate by selecting a plot of between 10 acres (4 ha) and 1 mile square in the vicinity of their home, or where they could visit regularly, and make winter visits in January and February and summer ones in May and June. The aim was to show the highest average number of each species likely to be encountered in an hourly visit, rather than the precise count on any particular day. What the response to this was is unknown.

Following a question as to how much space in the Annual Report should be devoted to rare vagrants, the Committee decided that the notes should concentrate on diagnostic features.

Several requests were received from members for beginners’ walks, so it was agreed to ask 20 members if they would be prepared to lead a monthly walk in their area, but most of those approached were somewhat unwilling to commit to this. Arrangements were eventually made for a team of the more knowledgeable members to lead at least one walk a month at places such as Bittell Reservoirs, the Lickey Hills or Sutton Park – a small charge being made for participation. No individual member would be asked to lead more than one walk a year.

One of the younger members, Eric Simms, also drew attention to the Cotswold scarp being an overland migration route between the Wash and the Severn estuary. To test his theory, a small group arranged to visit Meon Hill – an outlier of the Cotswold scarp – on September 17th. Given the distance and travel difficulties of the time, a dawn rendezvous of 6.15 am must have been quite challenging, even for those accustomed to military discipline. By 9.00 am 30 Meadow Pipits and a few other passerines had been recorded, mostly passing between the Hill and the main scarp. It was noted that the movement of Meadow Pipits over the Hill had first been noted two days previously, following large influxes on September 14th on the Isle of May and at Cley. These findings prompted members to suggest other possible ‘migrant lines’, most of which proved to be inconclusive.

On a more domestic note, it was agreed that the next meeting should include a supper at Clark’s Cafe. Discussion at this meeting focussed on which research projects to initiate and how to get members involved – perennial problems even today.

At the close of the decade membership stood at 399 – an incredible fivefold increase in just five years since the end of the war. The Secretary, Tony Norris. said “All along it has been my aim to get the membership figure over the 400 mark, for I feel that at that figure we can not only pay our way, but cover the three counties not too inadequately.”

He was nevertheless frustrated at the inability to attract members from outside Birmingham, and this became a recurring theme in his editorial comments. For instance, he wrote “as a Club we must face the fact that we still cover our area most inadequately” (1947): “as in previous years this (membership) increase has centred on Birmingham and membership in the country districts is still comparatively small” (1948): and “the main increase has come from the Birmingham area and our members are thin on the ground further afield. It is, however, to be hoped that the Branches now well established, and the founding of other Branches in the area, will do much to improve this position. (1949)”

These comments prompted us to look more closely at where members then lived, using the 1948 Report which was the last one to give members’ addresses. This revealed that 47% of members lived in Birmingham, 21% in Warwickshire, 17% in Worcestershire, 11% in Staffordshire and 4% elsewhere. These figures are broadly based on local authority areas as they were at that time, when Sutton Coldfield and Solihull were part of Warwickshire. Coventry was a separate authority, but for the purposes of our analysis we have included it in Warwickshire. Likewise, we have included Dudley – which ironically was a detached part of Worcestershire – as part of Staffordshire along with Smethwick, Walsall and Wolverhampton. Given the difficulties of travel, it was perhaps inevitable that Birmingham should have been so dominant. Further investigation, though, proved even more revealing, with just over half (52%) of the City’s members living in the south-western quadrant compared to 30% in the south-east, 12% in the north-west and just 6% in the north-east. This largely reflected the socio-economic structure of the time, with the south-western quadrant containing the university and affluent suburbs such as Edgbaston and Bournville as well as prime bird-watching haunts such as Rotton Park Reservoir, Edgbaston Park and Bartley Reservoir. Coupled to this Bittell Reservoirs and the Lickey Woods were also close by.

The 1950s

The most memorable event was unquestionably the Coronation in 1953, which heralded the new Elizabethan Age and a wave of optimism that better times were on the horizon. Yet the portends were not good. Two years previously the Government had promoted the ‘Festival of Britain’ as a post-war boost to morale. The intention was that this should be a nationwide event, with a major exhibition on London’s South Bank the focal point. At the time it certainly caught the imagination of the country, with huge numbers of visitors attracted to the exhibition. It even prompted one member of the Club’s Research Committee to ask what the Club was doing to support the event. The Club’s response was to enquire what action the BTO was taking, but there is no record of any response from either body! Quite what was expected by that Committee member is unknown.

Some improvements in living standards were beginning to emerge, but other constraints remained. Conscription, for example, remained throughout the decade and most young men, including some Club members, found themselves drawn into conflicts in more distant parts of the world. Indeed, the Club was directly affected when two successive Secretaries of the Research Committee felt obliged to resign in anticipation of receiving their call up papers.

It was not until the end of the decade that living standards really began to improve. By then, with rationing finally ending in 1954, there was a relative abundance of goods and freedom of choice. Many new products, such as refrigerators and washing machines were making life easier and more enjoyable, at least for those who could afford them. Sadly though, many couldn’t.

Perhaps the biggest changes to everyday life were the advent of television and the growth in car ownership. The Sutton Coldfield transmitter had begun broadcasting in 1949 and very soon most homes had a television set. Even though the pictures were only black-and-white and very small, for many television replaced the regular weekly trip to the cinema, or ‘pictures’ as it was called in those days. For some, though, it was a few years before television reached the more remote areas. Car ownership doubled in the decade following a huge drop in prices as Austin, Ford and Standard vied with one another to see which of them could produce the cheapest vehicles. As a consequence, many members became more mobile than ever before and were able to venture further afield in search of birds. The majority though, especially the young, were still reliant on public transport or the trusted bicycle for getting around. Moreover, leisure time for most was limited, as the majority were still working a five-and-a-half day week. In 1952 the average working week was 48-hours compared to the 37 hours of a typical week today.

The economy remained weak and, as the nation drifted in and out of recession, the Government placed a squeeze on credit. This resulted in considerable unrest in key industries, with ship builders, coal miners, bus crews and dockers all staging strikes at various times. Fortunately the West Midlands bucked the trend, as the increased demand for cars meant the motor industry remained relatively buoyant. Indeed, many came to this region from less fortunate parts of the country in search of work. However, the merger between Austin and Morris to form the British Motor Corporation was perhaps indicative of the motor industry’s vulnerability, as production of the iconic mini - launched at the end of the decade - was immediately disrupted by an unofficial strike. Even though emergency petrol rationing had ended in 1957, and the credit squeeze was lifted two years later, many still found it hard to identify with Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, when he claimed “most of our people have never had it so good”. Indeed, despite tax cuts in the budget and the Treasury saying the economy was now stronger than for many years, industrial unrest remained considerably high, with 15,000 on strike at the British Motor Corporation. Racial tensions were also beginning to emerge as unemployment levels were high and many blamed the ‘Windrush’ generation of immigrants for taking their jobs.

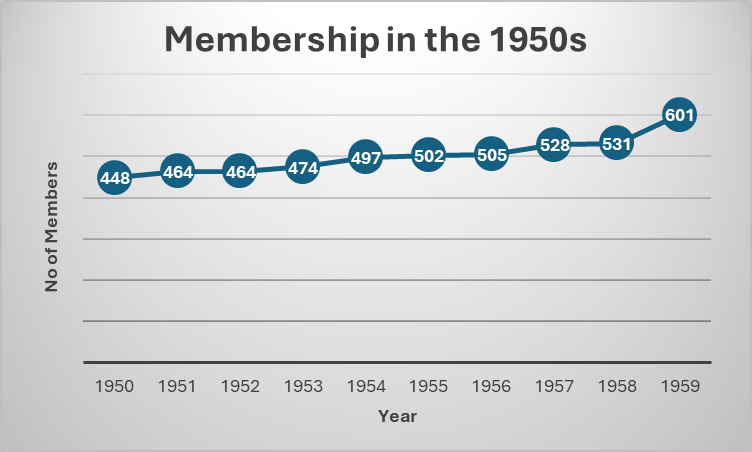

All this economic turmoil put tremendous pressure on family incomes and probably helped to explain why the dramatic fourfold growth in the Club’s membership over the second half of the 1940s reduced to a trickle overnight. The problem was not the failure to attract new members, but the difficulty of retaining those we already had – a situation that was not helped when the Club felt obliged to increase subscriptions to 12/6d from January 1st 1957 (a mere 63p in today’s money). During the four years 1956-59, 248 members left the Club – a figure that represented half the 1955 membership! In one year alone 10% of this loss was the result of having to strike off 25 members through non-payment of their subscriptions. As the Treasurer, Norman Swindells, remarked in his 1957 report, “these losses were in part offset by the new Stafford Branch, which had made a significant contribution by recruiting 23 new members during the year.”

Despite living standards failing to reach most people’s expectations, for the Bird Club this was a decade of prolific activity and a growing, enviable reputation. Foremost amongst the many new initiatives were a major new survey; expansion of ringing activity; formation of a new branch at Stafford in 1957; the first venture into conservation; and above all else securing Belvide as its first reserve and celebrating the Club’s Silver Jubilee in 1954.

Surveys and research have always been at the heart of the Club, much of which was done under the guidance of the Research Committee. Every year Club members have participated in the national wildfowl counts and the various BTO single species surveys. In 1950, however, the Club embarked on two exciting ventures of its own – one very successful, the other less so. The successful one was the landmark Breeding Bird Distribution Survey based on the Local Government areas in Staffordshire, Warwickshire and Worcestershire. The brainchild of the then Club Secretary, Editor and Research Committee Chairman, Tony Norris, this was a pioneering example of an atlas.

The highlight of 1951 was the publication of the results of this Survey. Its significance as a pioneering Atlas cannot be overstated. Although covering only 100 species, its impact was far reaching – so much so that in 1952 the BTO, no doubt influenced by Tony Norris, launched its own national survey of a limited number of species based on Ordnance Survey Grid squares.

Since very few copies of the ground-breaking 1950 survey survive, we will ultimately be including a photographic copy as as Appendix to our Story.

Organising such a survey had put added pressure on Tony Norris, however, so the Annual Report for that year was largely prepared by John Lord, who then took over the role of Editor in 1952 – a position he held until 1971. Tony Norris also stood down as Chairman of the Research Committee in 1950 and Brunsden Yapp took over the role.

The second, less successful, venture was again an idea put forward by Tony Norris and readily approved by the Research Committee. It was “to make possible a branch of research work not previously undertaken on such a large scale in such an inland area” by erecting a Heligoland trap for ringing birds. Over time this developed into a well-documented saga. To begin with there was the search for a suitable, accessible site, which had begun in 1949. This in itself posed a few problems, but the options were gradually whittled down to two, with a rickyard adjacent to an orchard on the edge of Birmingham finally being chosen. The original intention had been for the trap to be transportable – “the irony of which was not lost on those who witnessed the wind-blown state into which it had fallen the following year!” The next problem was to source materials – no easy task with post-war shortages of most things. Several members had offered to obtain quotes for the netting, but it ultimately fell to Tony Norris to contact John Barrett, at the distant Dale Fort Field Study Centre in Pembrokeshire, to enquire about his source for wire netting!

The netting was eventually obtained in February, and with members of the Research

Committee showing great enthusiasm, a basic structure was completed in a few weekends. Despite the lack of essentials, such as a door at the start of the tunnel and an amazing number of gaps in the netting, to which the birds were very adept at drawing attention, 60 birds were ringed in the first week and 456 of 17 species in the first year – a third of them (European) Greenfinches.

Most of these were caught whilst a blanket of snow was covering their natural food – an essential factor which became only too apparent the following year, when the trap proved not to have been the great success that had been hoped for. It was soon realised that the local birds had quickly learnt to avoid it, so reasonable numbers were only going to be caught in harsh winter weather, which of course restricted its value.

There was also debate as to who should pay for the rings - the ringer or the Club - and complaints about the accuracy of the scales being used for weighing birds. Having shown the existing ones to be inaccurate, Tony Norris said he could get some scales for 7/10d each wholesale. At this, one Research Committee member, Talbot Clay, suggested he should buy a dozen, sell to those ringers who wanted them and then “flog the rest from a barrow in Corporation Street.”

By this time (1950) G. Rayner had resigned as the Research Committee’s Secretary pending his call up for National Service, to be succeeded by Mike Rogers – a name that will be well known to many as a former Honorary Secretary of British Birds Rarities Committee. The next year Mike, too, had to retire pending his call-up and he was succeeded as Secretary by Tony Blake. Mike had a way with words and some of his quotes from the minutes regarding the Bartley trap make entertaining reading.

For a variety of reasons, repairs to the trap were proving to be a constant and costly necessity. As Mike records it, by the first summer it had been subjected to the “sadistic and uninhibited ravages of a local youth.” Later in the year he notes “the appearance on the scene of farm machinery resulted in the partial destruction of one end of the trap.” A reconstruction party had to be hastily arranged in order to remedy this. Finally, he reported that a cow had inadvertently wandered into the net, got itself caught and broken the netting to get free. His laconic summary of the whole saga was “the poor old thing (the trap) was now being subjected to the somewhat dubious interests of a cow on top of those of budding Tarzans and tractor drivers!”

At the time the location of the trap was kept secret to avoid disturbance, but later it became known that it was at Westminster Farm, Frankley, close to Bartley Reservoir on the edge of Birmingham. In expressing the Club’s sincere thanks to Mr J. F. Colewood for letting the Club use his land, Tony Norris wrote “We have had immense pleasure and obtained a great sense of satisfaction as a result of his co-operation. We hope neither our antics nor the arrival of the Birmingham press en masse on his land have inconvenienced him.” This seems something of an understatement given the events described above, though perhaps the media were a little more restrained then than they would be today.

Apart from the Heligoland trap, several other ringing expeditions were undertaken. Of these, those concerned with the controversial (Common) Starling were most noteworthy. Tony Norris said “In post war years the City of Birmingham has become famous, some would say infamous, for its attitude towards the Starling, some twenty thousand of which roosted in the City Centre during the winter, with smaller numbers in the summer. The fact that buildings are defaced and the noise of several hundred on the Town Hall disturbs the concert goers cannot be denied, but whether this constitutes such a public nuisance as to warrant the persistent demands for extermination by some of the City Councillors is quite another question. Happily the first six or seven rounds in the contest have gone unquestionably to the Starlings and only those few buildings that are electrically wired on the cattle-fence principle

have achieved immunity.” Various other attempts were made to dissuade (Common) Starlings from roosting on buildings in the City Centre, but mostly these met with little success. The Research Committee began what was to become a fairly regular count of birds roosting in the city centre (see the six areas on map opposite), the first of which found around 20,000 in the winter of 1949/50.

Outside the city, Eric Simms – a Club member who was destined to become a well-known personality especially as an author and broadcaster - discovered a huge roost near Shipston-on-Stour, which was visited more than once. In an age before mist-nets, it was said these expeditions “provided perhaps the most sporting aspects of a bird-watchers’ year. Working with 16ft (5m) high nets in complete darkness in the middle of a really dense, evil-smelling bramble and hawthorn thicket has to be experienced to be appreciated!” As an experiment in orientation, 63 of the 70 birds trapped at this location on November 27th 1951 were taken to Birmingham, kept in cages overnight and released from the top of the University Clock Tower between 15.00 - 16.00 hours the following day. On release, the birds followed every possible direction of flight – none making any attempt to join the flocks heading towards the city centre roost - though a gale force wind blowing at the time may have contributed to the random dispersal.

Pigeons too were perceived as a nuisance and Canon Bryan Green made a plea for people to stop feeding the birds in the churchyard. But Tony Norris pointed out that “the most common cause of trouble is, of course, the Starling …(but) they do not come into the city centre to feed, but only to roost.”

One (Common) Starling, ringed at the Birmingham Reference Library in 1952, was later found dead in Sweden. This prompted Tony Norris to note “this is the first concrete evidence we have had that our Birmingham Starling roost is in part, at least, composed of birds from the Continent. From this also it is clear that any methods of controlling the numbers of Starlings in Birmingham would have to consider the myriads of birds which come into this country each year and may, in any year, decide that the centre of Birmingham is a nice place to roost!”

The Club also took its first real step in conservation, when in conjunction with the RSPB it helped to get Alvecote Pools scheduled as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in 1955 and so secure their future, which was threatened by proposed opencast mining. The pools are now a Warwickshire Wildlife Trust reserve.

Branches were another of the Club’s innovations. The first two had been established in 1948 at Kidderminster and Studley. Credit for starting the Kidderminster Branch goes to Mr C. R. Millett, while its Secretary, Mr G. A. J. Weaver, organised a programme of indoor and field meetings. (we have found no details of these). These two Branches were quickly followed by the formation of two more - an East Warwickshire Branch at Coventry in 1950 and a South Warwickshire Branch at Stratford-on-Avon in 1951. The Annual Reports list the first Branch representatives on the Club’s main committee as C. R. Millett (Kidderminster from 1949), Miss M. Garstang (Studley from 1949), R. W. M. Lee (East Warwickshire from 1950) and Miss M. Hawkes (South Warwickshire from 1951). It should perhaps be mentioned that the Studley Branch, meeting in the College, was established long before Alan Richards moved to the village and he had no connections with it.

Apart from naming the branch representatives, however, the Annual Reports regrettably tell us little about the constitution and activities of these branches and the absence of Bulletins prior to April 1952 leaves a void in our knowledge of their activities. Even the post 1952 Bulletins include only occasional details of Branch meetings, yet the statement below implies there were more, at least in the Kidderminster Branch.

From the scant evidence we have, however, it would seem the branches had mixed fortunes. The Kidderminster Branch, no doubt supported by Tony Norris who lived at nearby Clent, flourished for many years, organising both indoor and field meetings, the former being held in the Town Hall. The East Warwickshire Branch, on the other hand, was very short-lived, closing in 1953, but for what reason is unknown. In contrast the South Warwickshire Branch proved more resilient, surviving until 1960, with Mrs M. Nelder taking over as its committee representative in 1955. What position she, and the other branch representatives, held within their respective branches is unknown.

However, we do know that the South Warwickshire Branch held an indoor meeting in 1952. Another fairly resilient branch was that at Studley, which we know held indoor meetings at the College courtesy of the Principal, Miss Garstang. It also held a field trip to Slimbridge in February 1958, organised by Audrey Knight at a cost of 9/- (45p in today’s money). Meanwhile Cecil Lambourne replaced Miss Garstang as the Branch Representative in1957 and the Branch survived at least until 1965.

The 1952 Report saw yet another innovation with the inclusion of photographs for the first time. Though only in black-and-white of course, the pictures taken by A. W. Ward and Stanton Whitaker were the first of many to grace our Annual Reports over the years - the Club being fortunate in having a string of eminent photographers amongst its membership.

The Research Committee continued to meet, though recruitment had become a problem. Tony Blake thought this was because membership was largely linked to the price of suppers and whether or not alcohol was free. To attract more members, it was resolved in 1953 to abandon Rule 1 of the Constitution, which required the annual election of members. By now there were already around twenty members, which was considered enough to ensure sufficient attendance at meetings, which were held firstly at Clark’s Café and later in Hudson’s bookshop canteen.

This Committee was very much like the origins of the Club, with members meeting as friends over a meal or a pint to discuss various aspects of bird watching. In later years individual members were asked to come prepared with a paper to stimulate discussion. Amongst the many topics raised, perhaps the most controversial was that advocated by one member, Norman Swindells, under the provocative title of ‘Ornithology is a Waste of Time’.

It was also observed that the Classified Notes for the 1949 Report had been slashed to make room for more articles. The Committee supported this action and proposed that it should be pursued in future years, with more space also set-aside for information on Field Meetings to encourage more people to go on them. Above the unanimous support for this proposal, the voice of Tony Norris was heard pointing out that “he maintained the right to do as he liked with the Report and did not propose to transform the Research Committee into a Board of Editors, although he still respected its resolutions.”

Research Committee members were also involved in field survey work in north-west Staffordshire for the BTO’s pilot atlas, and on Cannock Chase monitoring the after-effects of spraying by the Forestry commission to control an insect infestation. Help of a different kind was given to the Birmingham Museum when, in response to its request, Arthur Jacobs volunteered to assist in identifying the specimens in a recently acquired collection. Yet

another request was received for tape-recordings for an event on bird song to be held at Cannon Hill Park, Birmingham.

An insight into the informality of proceedings is provided by this quote from its Secretary, Tony Blake.

In 1953, Tony Norris and other Club members, together with the West Wales Field Society and local people, were instrumental in setting up the Bardsey Bird Observatory in what was then Caernarvonshire, now Gwynedd. The Club saw this not only as a new bird observatory, but also an opportunity for studying the complex ecology of a small island. Until recently, the Club had representatives on the Bardsey Bird and Field Observatory Committee, but following the adoption of new Charity Commission ruling this is no longer the case. However, it is understood that steps are being taken to reinstate more formal links between the two organisations.

At the time the Club’s members responded to a request for equipment for the observatory and Tony Norris said “It is proof of their generosity that I am now dictating this Bulletin (No 51) on the eve of my departure for the established observatory on the island. The house which we have leased, which incidentally had been empty for several years, has been repaired, redecorated from top to bottom, and is now quite luxurious. The furniture, beds and bedding have been purchased and installed, together with cookers and all the necessary miscellaneous equipment that goes to make a well-run household installed.” The Club, of course, has maintained close links with the observatory and the island ever since and has made further contributions in subsequent years, as will be seen much later.

Nationally, Club members lent their support to the Wild Bird Protection Bill, introduced into the House of Lords by Lady Tweedsmuir in 1953. Indeed, many members urged their MPs to support amendments that would have given even greater protection to birds, only to be disappointed with the 1954 Act when it eventually became law in December of that year. Most felt contacting their MPs had been a waste of time! It did bring some converts, however, with one member saying “I sold my gun and bought a pair of binoculars - what could be more sensible?”

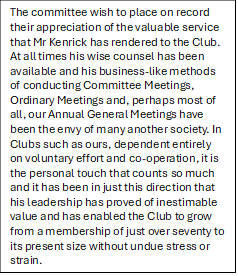

After seven years as Club Chairman, William E. Kenrick stood down in 1953. His successor,

Tony Norris paid the accompanying tribute to the outstanding contribution he had made. Following his election as the new Chairman, Tony Norris then resigned as the Club Secretary and was replaced by Tony Blake. By now secretarial duties were becoming more onerous, so a new post of Assistant Secretary was created with D. R. Mirams elected to fill it. A new Membership Leaflet was apparently produced around this time too, but we have not come across a copy of it.

The irrepressible Tony Norris also brought a supply of nest-boxes along to indoor meetings for sale at 7/6d. as well as arranging for a stock of current BTO literature to be made available. Mr J. T. Baron kindly agreed to organise this latter service, which it was thought would be of help to members, but it’s not clear how long this persisted.

The Jubilee Year in 1954 fittingly saw further new developments. It began with a new heading for the Bulletin that incorporated the Club’s first ever logo – an outline of the three county boundaries - flanked by details of the Club’s officers (see below). At the time this was considered a contemporary design reflecting a more modern age, but in reality it just reduced the space available for news in the Bulletin!